by James Breig

– Dave Doody

Photo courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Eighteenth-century Americans enjoyed blessings in disguise and built castles in the air, but none lived on Easy Street or ever put on the dog. They kicked the bucket but never knocked at the pearly gates. They knew mum’s the word, but kept nothing under their hats. Which is to say that they enriched their speech with idiomatic expressions that still trip from our tongues, but that some of the colonial derivations given for old folk phrases turn out to ring hollow.

“Blessings in disguise” is a British expression recorded in 1746 and a phrase that could well have been used in colonial Williamsburg. So could have “castles in the air,” an expression that dates to the sixteenth century. “Easy Street,” however, did not grace the language until 1901, in the book Peck’s Red-headed Boy, and “putting on the dog” is a nineteenth-century coinage. “Kicking the bucket” is defined as dying in the Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, published in 1785 by Francis Grose. But “pearly gates” did not signify the entrance of heaven until just before the Civil War. William Shakespeare wrote of “keeping your own counsel,” in Hamlet, 1602, and “mum’s the word” is recorded in 1704. But we did not begin to “keep things under our hat” until about the 1940s.

Adventures down the byways of our language are, of course, among the things that attract us to the streets of Colonial Williamsburg. Visitors can travel back in time by riding in carriages, donning three-cornered hats, and admiring a gunsmith make a musket or a silversmith etch a salver. But among the more cerebral ways to recapture the feeling of the eighteenth century is to listen to costumed interpreters speak the words and phrases of that bygone time and to distinguish them from ours.

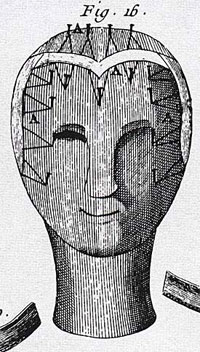

“Blockhead” derives from wooden forms used to make and maintain wigs.

Photo courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

In a sense, eighteenth-century English is a foreign language, and learning to use idioms deepens the understanding of a tongue. Though Americans of that era had expressions and sayings we use today—such as “one foot in the grave,” “the powers that be,” and “waste not, want not”—they also employed slang, clichés, and idioms that would baffle us. For example, Gouverneur Morris, an early United States ambassador to France, told William Short, a Virginia protégé of Thomas Jefferson, not to “kick against the pricks,” and John Adams, writing from Europe, informed his wife, Abigail, in Massachusetts that he would take a “virgin” to bed if he got cold. Morris meant that Short shouldn’t fight a cause that is lost and Adams was employing a British vulgarism for a hot-water bottle, something he explained later in his letter to the distant Abigail.

Where the street is named for the Duke of Gloucester, the man in the street—an early nineteenth-century idiom—has a lot to learn about colonial neologisms and Virginia verbalizations. Interpreters don lutestrings, an eighteenth-century dress of glossy silk, and spencers, a kind of wig, and pepper their conversations with words like “blockhead,” a term derived from the wooden wig stands used in the 1700s. They also take care to avoid linguistic old wives’ tales—an expression in use in the eighteenth century.

Myths arise and get passed about as gospel, a process sped up, extended, and given a sheen of authority by the Internet. For instance, though “blockhead” is an authentic expression, “flipping one’s wig” did not appear until the twentieth century.

“Sleep tight” does not trace to beds with ropes pulled taut by such tools as the one shown.

– Dave Doody

Photo courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Many a visitor to bedrooms in the homes of Colonial Williamsburg has been told that “sleep tight” derives from tightening the ropes on which mattresses rested 250 years ago. It makes a good story, but it’s not true. “Tight,” as an adverb, means “soundly,” “snugly,” or “closely,” so the expression means “sleep well.” This use has lasted into our times, as anyone knows who has seen The Wizard of Oz. Glinda the Good Witch tells Dorothy to “keep tight” inside her ruby slippers. And who hasn’t responded to a telephone caller asking for help by saying, “Sit tight; I’ll be right over.”

There is a propensity not to let the facts stand in the way of a good story, and the enchantment of folk etymologies is sometimes so strong that boneheaded derivations are cheerfully propagated by people who know better, or have at least cause to. Sold in Williamsburg is a durable old pamphlet about eighteenth-century expressions that, after disclaiming pretension to academic accuracy, retails, pig-in-a-poke, word origins collected willy-nilly from tourists and guides. By the way, Chaucer gets credit for recording “pig in a poke” and “willy-nilly” was put to paper by Middleton in 1608.

A “powder room,” as the booklet says, was a closet where a man or woman of the 1700s could have a wig repowdered, and “slipshod” did mean “shod in slippers” and therefore slovenly. So far, so good. But the author says “big shot” derives from colonial cannon being fired when someone important came to town. In fact, the term wasn’t used in America until the 1920s. Nor does “spooning” come from young eighteenth-century men whittling spoons to keep their hands occupied while courting. The word came into use in the 1870s.

A “powder room” was an apartment where wigs were dressed.

Photo courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

A more popular gaffe is “putting on the dog,” which the booklet says came from a colonial custom of making shoes or gloves out of dog skin. That sounds like a fascinating fact from our pre-Revolutionary past, but research in sources like the Oxford English Dictionaryshows the expression is no older than the 1860s and probably traces to wealthy people with lapdogs. An 1871 reminiscence titled Four Years at Yaledemonstrates that the phrase had become college slang by that time. The book says: “To put on dog is to make a flashy display, to cut a swell.”

Faulty derivations can also be found in such more serious works as Common Phrases and Where They Came From, published in 2001. It says eighteenth- and nineteenth-century phrases like “not giving a damn” and “not worth a damn” refer not to damnation but to a monetary unit in India that had little value. The Oxford English Dictionarysays such an explanation is “ingenious but has no basis in fact.” It dismisses the theory that the expression is a shortening of “don’t give a tinker’s damn,” recorded in 1839 by Henry David Thoreau. A tinker’s dam is a bowl of dough shaped by a tinker that keeps solder from running off his work area. The dough is used once and discarded, making it worthless. The notion that people observed this and then punned, “I don’t give a tinker’s dam,” says the dictionary, is “baseless conjecture.” The expression more likely arises from the propensity of tinkers, like sailors, to curse profusely, making their oaths too common to have power or effect.

The small, slovenly man at left in this 1736 Hogarth print is abroad in his slippers, and thus “slipshod.”

Photo courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

With no eighteenth-century audio recordings on which to rely, researchers turn to printed material for accurate reconstruction of eighteenth-century speechways. They pore over letters, diaries, novels, and other documents for expressions to determine when they were in vogue and the context in which they were used. The work is not easy, but it is getting less tedious, according to Linda and Roger Flavell, experts in idioms and co-authors of The Chronology of Words and Phrases and Dictionary of Proverbs and Their Origins.

Responding to e-mailed inquiries, they said: “The researcher has to look at the extant records: the written word. One can go to primary sources, the texts themselves, and look for relevant expressions. This is made much easier these days by the availability of digital texts, which are simple to search. Secondary sources—dictionaries, glossaries, contemporary grammars, etc.—can cut down the ‘leg work’ dramatically. But that is not the end of the matter. There are other questions: What exactly did the expression mean at the time? How does it relate to contemporary culture and practices? Has it undergone shifts in meaning, form or function since its early appearances?”

Discerning when an idiom began—or at least when it was written down—is often easy; discovering where it came from is a horse of another color—a saying used in America since at least 1798. Anyone checking theOxford English Dictionarywill find sayings labeled “origin obscure.” In other cases, conflicting explanations are offered to show at least something of how an expression arose. Some expressions have a clear genesis. The eighteenth-century British poet William Cowper gets credit for creating expressions you might think have been around for ages: “God moves in mysterious ways,” “the worse for wear,” and “variety is the spice of life.” Other sayings have births just as plain but go through evolutionary modification. Calling someone a “goody twoshoes,” which became colloquial in 1934, traces to a 1765 nursery story about a character named “Little Goody Two-Shoes.” “Goody” is a shortened version of “goodwife,” a style of formal address. Succeeding generations transformed “goody” into an adjective and then a pejorative.

The iron pots hanging in the fireplace might with justice call the sooty copper kettle black, or little better than they.

Photo courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

It is not far to seek eighteenth-century expressions in straightforward twenty-first century use. A perusal of the Pennsylvania Gazetteturns up “many hands make light work” in 1787, “live and let live” in 1772, and “honesty is the best policy” in 1768. Everyone since the 1500s has sometimes been “down in the dumps,” a phrase in use at least since then. But other phrases from colonial times are foreign to modern ears. Twenty-first-century Americans talk of having a sore throat; Adams would say he “caught the pip.” The meanings of other sayings have been altered. To people in the 1700s, “burning the candle at both ends” meant foolishly spending all of one’s savings. Three centuries later, it means taxing not your fiscal but your physical stamina.

Then there is the matter of wild oats and wild grapes, either of which could signify a dissolute youth. In his memoirs, John Woolman, an eighteenth-century New Jersey Quaker and abolitionist, regretted that, at age sixteen, “I perceived a plant in me which produced much wild grapes.” The Oxfordeditors cite that expression as early as a 1547 sermon that defined them as “sour works, unsweet, unsavoury, and unfruitful.” Modern Americans are more familiar with wild oats, which sprouted almost as early—in 1576. In his eighteenth-century novel Captain Singleton, Daniel Defoe writes: “Thus ended my first harvest of wild oats.”

The Flavells say that “the mainly rural life of the times certainly means that agricultural expressions, phrases about the weather, etc. were more common than today. One might also say that the growth in shipping led to the introduction of various nautical expressions.”

But neither boats nor beans explain some expressions. Whether referring to military strategy or political maneuvering, George Washington liked to say or write, as he did in 1793, that “there is no adage more true than an old Scotch one, that ‘many mickles make a muckle.'” Anyone who heard him use the saying knew what he meant: If you attend to the small things, the big thing will be taken care of. The problem, according to Bartlett Jere Whiting, who wrote Early American Proverbs and Proverbial Phrases, is that the expression has “the almost fatal flaw of failure to make sense.” In Washington’s mind, “mickles” were small things that added up to a big thing, a “muckle.” Whiting says “mickle is a large amount and muckle is a dialect variant of mickle, with no change of meaning. Thus Washington’s adage means that ‘Many greats make a great,’ which is not what he had in mind.”

Interpreter Beverly Henry spins at a “muckle,” or walking wheel, at right, the term being something of an all-purpose word for large.

Photo courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Regardless, the expression suited the first president “to a T,” an idiom found as early as 1693. People in the eighteenth century were just as likely to say “to a hair” or “to a hair’s breadth” to indicate how closely two things fit. Shakespeare used the expression in The Merry Wives of Windsor. “Egad,” you might say on learning that, and you would be employing an eighteenth-century interjection, one of many that softened such references to the divinity as “Oh, God.” In the same way, modern people avoid “Jesus” by muttering “jeez,” a form that first appeared in the 1920s. A Colonial Williamsburg fact sheet for character interpreters says they will be historically correct if they use the expletive “Oh, La” or “Lard” instead of “Lord” or cry, “Zounds” in place of “by God’s wounds.” Men and women of that time even shouted, “Fudge,” but it was not a substitute for another F-word. It meant “nonsense.”

This softening is an expression of gentility, the Flavells say. A 1752 article in the Pennsylvania Gazetterenders a familiar proverb: “The kettle should not call the pot black a—-.” The use of the word “arse,” the Flavells say, “was regarded then as too vulgar for polite conversation. Such decencies can vary in relation to the climate of the time and to the sensitivity of an individual. This is very obvious in spoken language today; there are many speakers who will not, even now, use many taboo forms.”

Williamsburg’s citizens also had roundabout ways of talking about sex, employing “die” to mean “have an orgasm” and “lie with” in place of cruder terms for sexual intercourse

In the 1700s, as the Colonial Williamsburg document notes, people could choose from an assortment of insults. A loose woman was “baggage” or “a hussy.” A foolish young man was “a puppy.” A coward, then as now, was “a chicken,” a term the Bard of Avon employed. As for impugning someone’s intelligence, eighteenth-century people could select not only “blockhead” but “idiot,” recorded in 1377; “dolt,” 1543; “dummy,” 1598; and “numskull,” used by Jonathan Swift in 1724. They did not, however, have the options of “moron,” 1910; “jerk,” 1935; or “stooge,” 1913.

With such information in mind and on the tongue, a person of the past—whether “poor as a church mouse,” which dates to 1731, or “rich as Croesus,” in use by 1707—can stroll about Colonial Williamsburg better prepared to present the eighteenth century. Even if it’s “raining cats and dogs,” as it has been since the 1700s.

James Breig is an Albany, New York, writer and editor and contributor to the Colonial Williamsburg Journal.