by Joe Wagner

Logistics: “. . the branch of military science dealing with the procurement, maintenance, and movement of equipment, supplies, and personnel.”

PART ONE – THE QUARTERMASTER GENERAL

The Continental winter camp at Valley Forge in 1777- 78 is the stuff of legend. A pitiable, cold, starving army in rags perseveres through all hardship to emerge in the spring ready to fight and win. Skeptics will point out that it really wasn’t all that tough a winter from a meteorologi- cal point of view; the succeeding winter at Morristown, NJ was far more intense. But for the men who were there, it was a time of real hardship. More than the cold, the lack of clothing, food, fuel, and every necessity of life were made more bitter by the knowledge that the British were only a few miles away in the warmth and comfort of their late capitol, Philadelphia. Why the logistical failure at Valley Forge –why the inability of the Continentals to support themselves in the field?

With this article we start a four-part series in Dispatches on logistics of the Continental Army – – the planning and execution necessary to support an American army in the field. It will give you information for your reenact- ment and interpretation of that world of 250 years ago. Easy enough to call up the militia, appoint the generals and colonels, and plan a campaign. But who brings the ammo and the flints? Where are the tents and kitchen gear? Who collects the food? Where are the wagons and carts to carry everything? Where do the horses and oxen come from to pull the wagons – and who feeds those? How does an army stay in one place for months and not suck dry the surrounding countryside? Or how does it move twenty miles, or two hundred, and expect to find everything it needs along the way and at the other end? And how did a collection of colonies with no experience or logistics structure instantaneously create the people and processes necessary to do all of these things and a million more?

The coming installments on Logistics are:

- Part I. The Quartermaster General

- Part II. Transport and Forage

- Part III. Subsistence and Clothing

- Part IV. Ordinance

THE QUARTERMASTER GENERAL

It’s to the credit of the Continental Congress that within weeks of the April 1775 deployment of an American militia army at Boston, they authorized creation of the necessary staff offices to provide for the Army’s needs. Even before Washington arrived to take command, in June and July 1775 Congress authorized appointment of a Quartermaster General (actually with the rank of Colonel), and a Commissary General of Stores and Provisions. They later added a Hospital Department, Commissary of Military Stores (Ordinance), and a Clothier General. It was left to the new Commander the task of actually filling these positions, and those of other specialists who would work under them. We’ll begin in this issue with what the Continental Congress and the army began with – the first essential ingredients of army logistics – a Quartermaster General (QMG).

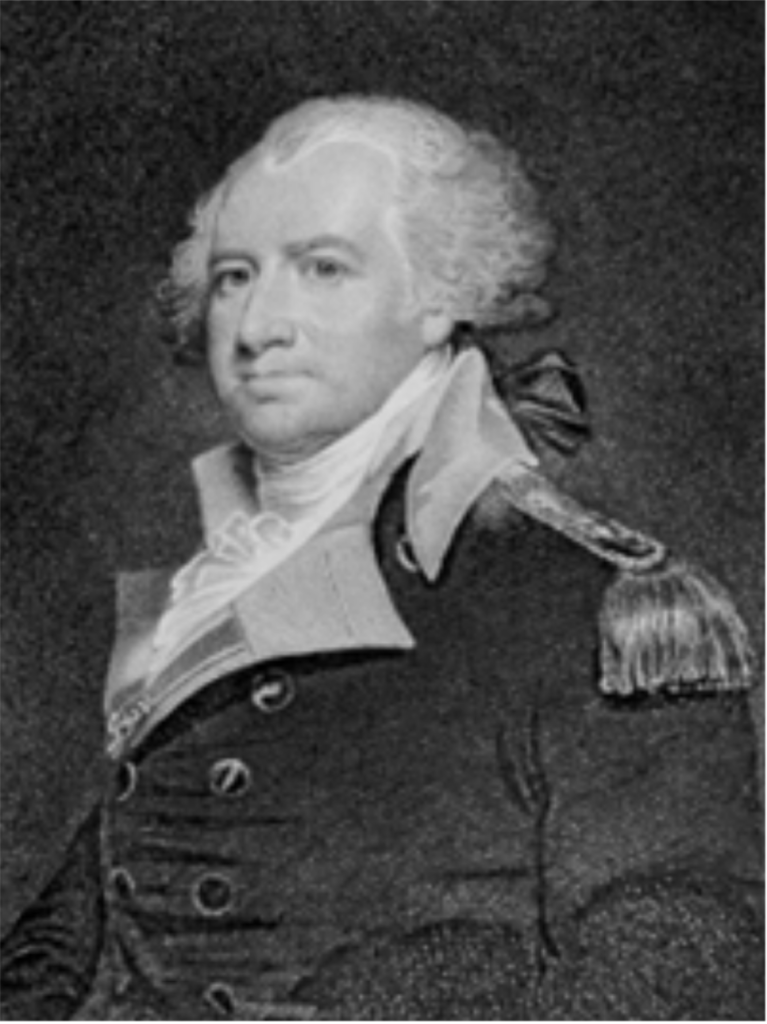

Washington filled this most important logistical position in August 1775 with appointment of Major Thomas Mifflin, a 31-year-old Philadelphia merchant then serving as one of his aides. Mifflin’s tenure represents the first of three QMG phases in the history of the Continental Army.

The Mifflin Era: August 1775 – October 1777

Exactly what did a QMG do? The definition in the 18th century was essentially that of Chief of Staff, responsible for almost every aspect of the army’s existence. The following list is indicative of the job as Mifflin developed it in 1775. Later QMGs split the duties into lesser depart- ments and subordinate offices. But in the beginning, when the army was stationary and closely grouped around Boston, Mifflin oversaw everything.

The scope of the QMG included gathering intelligence on enemy movements and plans; planning troop marches and deployments; distribution of movement and supply orders; opening and repair of roads; provision for water transport – bridges or boats; laying out of the camp and its defenses; the procurement of camp equipment, tents, lumber, etc; provision of firewood; procurement of horses, oxen, pack animals, and their forage; provision and maintenance of transport wagons, carts, packing cases and leather gear; and over all, providing the commander with a staff director to coordinate any and all other activities.

It’s important here to note the several large areas of re- sponsibility not under his jurisdiction. One was Ordinance. Duties of the QMG applied only to supporting the needs of the troops of the line. The QMG did not play in the business of artillery, munitions, and related services. That job was under the control of the Commis- sary of Military Stores, who would report to the Chief of Artillery. We’ll discuss him in Part IV of this series. Another piece missing from the QMG’s pie was person- nel management. He did not take care of the individual troops in terms of enlistments, promotions, pay, discipline, etc. That role belonged to the Adjutant General.

When Congress authorized a QMG for the main army at Boston, it also shortly established a policy to designate deputy QMGs to serve in expected geographical departments (northern, central, and southern) and assistant QMGs to serve with any other armies fielded besides the main forces under Washington. As things developed, the QMG structure included deputies appointed for a northern department (New England and Canada), and the states of the southern department (Virginia, Carolinas, Georgia). Other assistant QMGs were established with specific forces, such as Gates’ northern army and Greene’s southern army, when those came into existence. Later, each army brigade would designate a QMG to provide for the battalions of that unit. Needless to say, the potential for overlapping and disconnected exercise of responsibilities was inevi- table, since there were both geographic and unit – based QMGs working in the same locations to service the same forces.

At Boston, Mifflin set up three field offices to provide logistics services to the army. Since the army was in static positions, many of the functions related to troop move- ment were not required, yet. To provide QM support to the 17,000-man army, Mifflin’s immediate organization was staffed by a total of 28 officers, enlisted men, and civilians. We can understand their tasks by reading their titles. These included clerks of accounts, camp equipment clerks, (fire) woodsmen, lumberyard supervisors, smiths, armorers, nailers, carpenters, wagon masters, and barrack masters. In addition, Mifflin utilized various merchants in the area of Boston to serve as his purchasing agents for every kind of good needed. They received a commission of 2% for everything delivered to the army. While this staff organized and managed the logistical support efforts, there were obviously innumerable workers among the troops and hired civilians who aided in accomplishing the many tasks of supply.

As the war moved from Boston to New York, and then to the Jerseys, Mifflin and his staff moved with them. He briefly was nominated for a field command, to be replaced by Stephen Moylan – a shipping merchant. But he had done such a good job that members of Congress and Washington himself prevailed upon Mifflin to stay with the QMG assignment. During 1776 – 77 Philadelphia became the center of Mifflin’s efforts to collect and distribute supplies and equipment to the army. It also became the focus of his efforts to further develop his organization. He lobbied Congress, and with Washing- ton’s support, it enacted legislation for several new offices reporting to the QMG. Congress created the Forage and Wagon departments, and authorized Mifflin to select a Deputy and other assistants to lead the subordinate offic- es. From the end of 1776, Mifflin spent little actual time in the field with the army. He appointed his Deputy, Col. Henry Lutterloh, as the commanding officer in the field for the QM organization.

No complete organizational plan or unit return for the QMG survives from this period, but fragmentary evidence shows a fairly well developed operation for supporting Continental forces, both with the main army and elsewhere. The concept was to develop a widespread web of purchasing agents responsible for obtaining sup- plies from across the colonies, particularly in the better- developed and prosperous areas, such as the counties just west of Philadelphia. These supplies and equipment would be transported by the QM department via roads or water to the operating location(s) of the army, or to any other designated point, such as the selected location of the coming winter’s camp. Of course, a flow of sup- plies required a continuing flow of funds from Congress or the colonies. Mifflin maintained a small office with a Colonel and four assistants in Philadelphia, to deal with Congress, handle correspondence with the field, and to coordinate supply collections and deliveries in the capital. There were deputy QMG offices in Albany (Northern Department), Boston (Eastern Department), Fishkill, NY (Washington’s army), and Williamsburg, VA (Southern Department). Also, assistant deputies QMGs were located in areas where Mifflin had established sup- ply sources, mostly in the counties around Philadelphia. These included Easton, Reading, Carlisle, and Lancaster, plus Wilmington, DE.

Mifflin had created a pipeline process whereby funds from Congress were sent to the QMG agents around the colonies, who bought supplies and equipment from local merchants and artificers, and then had them transported to the QMG organization at the army’s current or future location. The geographically located QMGs and the subordinate agents would work at either end of the pro- cess, serving as supply sources for materials and products originating in their own areas, and then forwarding them to the needed location. If the army was to be in their area of responsibility, they would serve as the receiving agent to accept the supplies flowing from more distant locations.

The financing for this system came directly from Con- gress. While they might get by with not paying the troops for months or years, the delivery of food, tents, and transport required the funds necessary for immediate payment. The patriotism of most merchants and traders of the colonies did not extend to bankrupting themselves to supply the army’s needs. In the beginning, funding and in-kind supplies provided by the colonies to Con- gress did a reasonable job of meeting the needs of the army, and Mifflin did a creditable job of supplying the army through the campaign of 1777. We will see what he and his successors accomplished in more detail in the next three parts of this series.

But Mifflin was not an enthusiastic QMG. He had always wanted a field command (and a Generalship), and had never felt dedicated to the task of supply manager. With the British capture of Philadelphia in the fall of 1777, Congress fled to York, PA, and Mifflin, his orga- nization disrupted, fled to Reading Pennsylvania. There he was overtaken by a deep depression. He pleaded with Congressional friends to allow him to quit the job of QMG and gain a field command. Thus began the events that would make the winter of 177-78 at Valley Forge among the darkest hours for the American army.

Mifflin told Congress he was resigning as QMG, field command or no. In November 1777, Congress ac- cepted his resignation, but asked Mifflin to continue in service until a successor was appointed. Washington was informed of this development, and the Deputy QMG, Lutterlow, was to continue to provide support in the field. But Mifflin refused to continue as acting QMG. He completely abandoned his post, telling Congress, but not informing Washington or Colonel Lutterlow.

It would take Congress four months to select the next QMG, and in the interim, there was no one in charge of the supply process that should have been preparing for the winter camp of 1777-78. For several months, as far as can be determined now, Washington thought Mifflin was still working to prepare the winter camp. By the time Washington and Lutterlow found out that Mifflin was gone, it was too late. Lutterlow, in the field with Washington, did not have Mifflin’s contacts or access to funds to prepare a supply buildup at the winter camp.

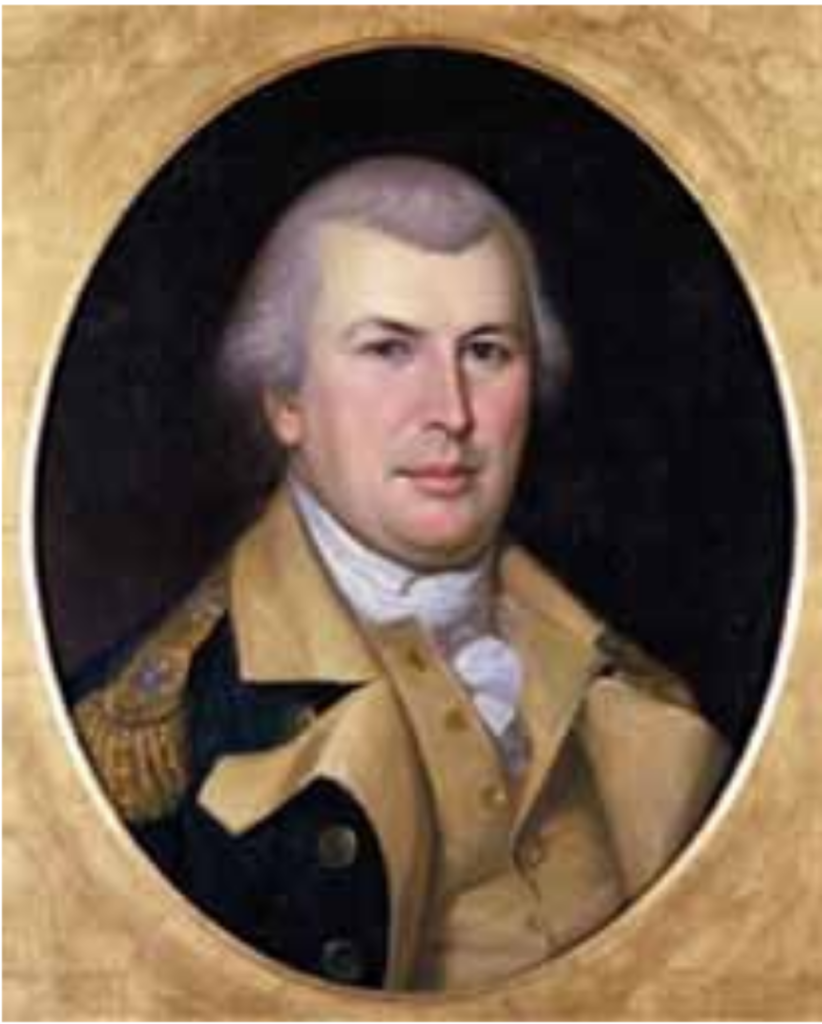

Washington had no one to turn to for coordination of purchases, collection, and transport from distant points to his winter quarters. Congress, and most of its staff, were scattered around western Pennsylvania. The result – when the army moved in to the Valley Forge encamp- ment, there were no supplies, no transport, no forage for animals, and no planning or arrangements of any kind for logistical needs in the months ahead. It was not until March 1778 that a committee from Congress, visiting the camp, and appalled at conditions, begged General Nathaniel Greene to accept the post of QMG. Greene, a brilliant field commander, took the job for only one reason. Washington joined Congress in begging him to assume the post, and Greene accepted out of his personal loyalty and devotion to Washington. And so a second unwilling officer is drafted as QMG.

The Greene Era:

March 1778 – August 1780

Major General Nathaniel Green assumed his duties in March 1778. Member of a prosperous manufacturing family from Rhode Island, he was knowledgeable in the needs of fund- ing, purchasing, and other supply concepts. He immediately renewed and expanded the staff and operating concepts of Mifflin. Unlike Mifflin, Greene stayed with Washington in the field. He established a quartermaster representative with each brigade of the army, and selected a staff of his own consisting of a deputy, a wagon master, a commissary general, and auditor of accounts, and various clerks. He assigned one of his immediate assistants, Charles Petit, to establish an office in Philadelphia once the city was liberated, and assigned another, John Cox, as his traveling agent for purchases and inspector of stores. He did not change the concept of assistant QMGs in the geographic departments, nor the use of deputies serving as agents for procurement in the counties of Pennsylvania and other areas. In fact, the organization grew to such size that Congress and Greene’s critics soon accused him of creating an empire. If there was one thing Greene could do, it was build the bureaucracy!

The reports to Congress of these excesses provide the kind of interesting details that otherwise would not be available for us two hundred plus years later. In Philadelphia alone, Greene had a deputy, John Mitchell, who employed a bookkeeper, a cashkeeper, several messengers and clerks, three porters, an assistant for boats, who in turn employed the masters, mates, and complete crews for three schooners, a wagon master general and six wagon masters, a superintendent of wood and boards, superintendent of barracks, superintendent of stables, plus 25 or so other employees such as wheelwrights, hostlers, and conductors. (We find out what a conduc- tor does in Part II.) Greene also grew the organization at the state level. Along with the department QMGs, he developed deputies and assistants in the various states, each with their own staffs numbering, on average, about 30 to 40 individuals. By 1780, the grand total, as best we can determine now, amounted to the QMG (Green), two assistant QMGs, 28 deputy QMGs, 109 assis- tant deputy QMGs, and a total staff in all departments and functions of over 3,000. This, at a time when the army, on average, numbered 10,000, and never exceeded about 24,000. It’s only fair to understand that this quantity of staff was spread over the entire geographic area of the coun- try, and their job was to gather the products and resources of the colonies and get them to the armies wherever needed. Nonetheless, it appears a lot of empire building was going on.

At a time when the QMG was growing, its ability to provide for the army was rapidly diminished, through no fault of its own. Although supplying the army’s needs for the campaign of 1778 was accomplished, and Washington was satisfied with Greene’s performance, the financial situation for Congress was reaching a crisis. Having run out of funds backed by hard currency, the Congress and the states were beginning to rely exclu- sively on paper specie, backed only by the promises of the government. The inevitable result was hyperinflation and the finances of the QMG were soon “not worth a Continental”.

“The cloud thickens, and the prospects are daily grow-

Letter: Greene to Washington, December 1780

ing darker. There is now no hope of cash. The agents are loaded with heavy debts, and perplexed with half-finished contracts, and the people clamorous of their pay, refusing to proceed in the public business unless their present demands are discharged. The constant run of expenses, incident to the department, presses hard for further credit, or immediate supplies of money. To extend one is impossible; to obtain the other, we have not the least prospect. I see nothing, therefore, but a general check, if not an absolute stop, to the progress of every branch of business in the whole department. It is folly to expect that this expensive department can be long supported on credit.”

The combination of bloated staff combined with the ballooning budget requirements, brought unwelcome attention from Congress to Greene and his operations. He had successfully completed logistical support for the campaign of 1779. But Congressional investigation of the size of his staff, accusations of excessive commissions being earned by his agents, and the financial crisis caused by the worthless currency and credit of the colonies, brought an end for Greene as the QMG. Congress ad- dressed both of the perceived problems – staff size and financial failure. They told Greene to reduce his staff and change the way his agents were paid. To reduce the costs of the department, they also took away two of the major QM responsibilities – provision of forage, and provision of transport. These were handed over to the individual colonies, to be apportioned among them based on the forces located within their territory. With this wholesale destruction of his organization, Greene did what Congress fully expected – he resigned August 5th, 1780. Fortunately, there was no major campaign by the main army in the summer of 1780, and the depar- ture of Greene, with a two month delay until his replace- ment arrived, did not cause Washington a hardship.

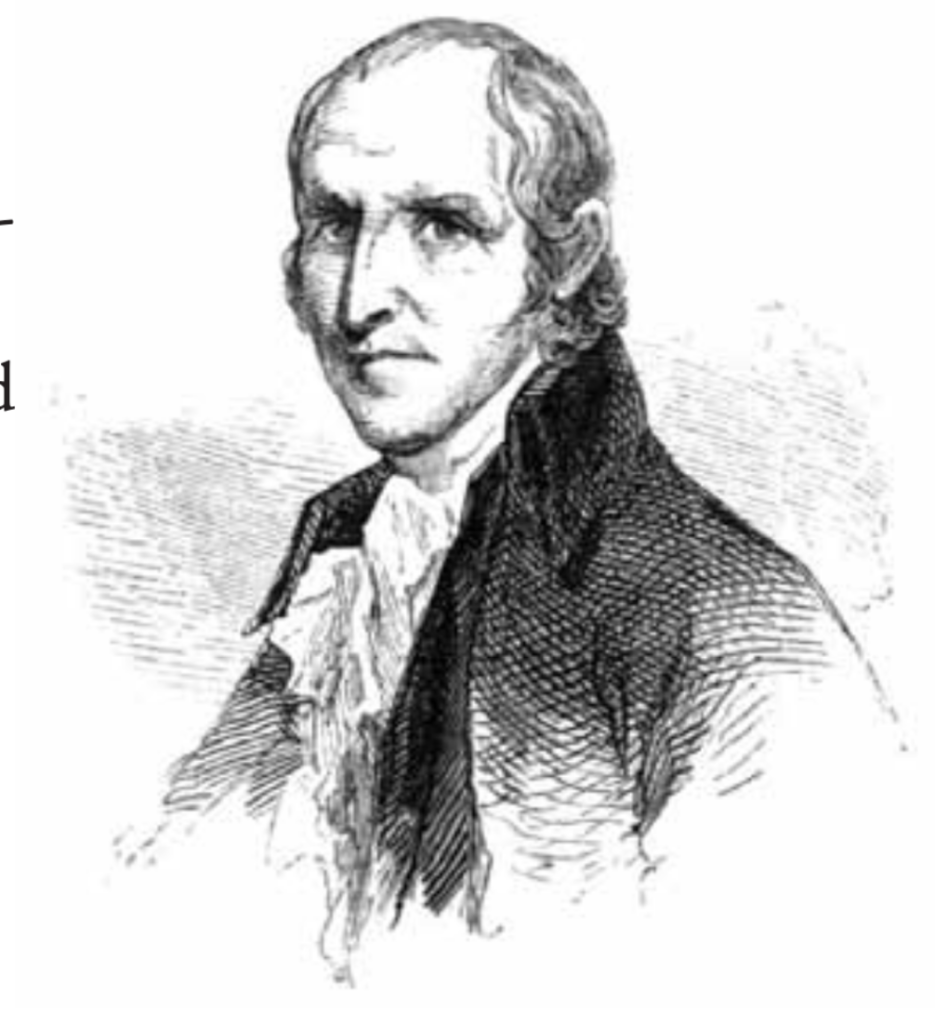

The Pickering Era: October 1780 – July 1785

Colonel Timothy Pickering was a lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, was serving as the Adjutant General, and also as a member of the Continental Congress’s Board of War. He was one of those very critical of Greene’s management of the QMG, and he was not enthusiastic to find himself placed in the same position, facing the same problems. But he began with acceptance of the politi- cal climate, which called for downsizing and frugality. He reduced the number of deputies and assistants, for example combining the Pennsylvania organization’s 7 or 8 assistants down to a single deputy.

Pickering found the conduct of Quartermaster business handicapped by the lack of credit and the effects of a de- preciated currency. Fully aware of these difficulties at the time of his appointment, he proposed the use of ‘’specie certificates,” which called for payment in specie at a given date for all articles or services purchased on credit. In effect, he sought credit from suppliers, but credit which could be circulated. If payment was delayed, such certificates were to bear an interest rate of 6 per cent a year until paid. Congress authorized their use; thereby enabling Pickering to obtain a few more supplies than would otherwise have been possible.

Often Pickering would have to fall back on a last and most desperate measure to supply the army – an impressment warrant. Whenever the need for supplies or material reached a critical point, and the finances were lacking, the QMG would go to Washington and request a warrant for the impressment – seizure – of the needed items from the surrounding countryside. This tactic was employed more and more often as the war continued, and the finances of the Congress and colonies became more desperate. Throughout the war, however, Pickering continued to be so plagued by the lack of funds that he wrote Congress: “If any other man can, without money, carry on the extensive business of this department, I wish most sincerely he would take my place. I confess myself incapable of doing it.”

Harassed by lack of funds and scarcity of supplies, Pickering nevertheless, in consultation with Washington and acting in the double capacity of consulting member of the Board of War and Quartermaster General of the Army, achieved one of the greatest logistical accomplish- ments of the war. He provided for the successful trans- portation, mostly by water, of the entire American and

French force from the Hudson in New York to the James River in Virginia for the siege of Yorktown and the cap- ture of Cornwallis. We’ll learn more of this feat in the next installment of this series – “Transport and Forage”.

After Yorktown, Pickering continued to serve for the remainder of the war. For the most part, he was concerned with affecting various economies in the Quartermaster’s Department and attempting to settle his accounts as quickly as possible. He wrote Robert Morris that ‘’until I accepted this cursed office, though necessity compelled me to live frugally, yet I had the satisfaction of keeping nearly clear of private debts,” that he was now much indebted. He wanted nothing more than a quick settle- ment of accounts and an opportunity to return to private life, where he might set about repairing the fortunes of his family. This settlement dragged on for many months after the war had ended, and Pickering did not relinquish his post until the Quartermaster’s Department was abol- ished on July 25, 1785.

Stay tuned for the next installment – Part II – Transport and Forage